Missing flight: Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370/MAS370) was a Malaysia Airlines international passenger flight that went missing on March 8, 2014, while travelling from Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia to its scheduled destination, Beijing Capital International Airport. The crew of the Boeing 777-200ER, registered as 9M-MRO, last interacted with air traffic control (ATC) about 38 minutes after takeoff, while the plane was flying over the South China Sea. The plane vanished from ATC radar screens minutes later, but it was monitored by military radar for another hour, veering west from its original flight path and crossing the Malay Peninsula and the Andaman Sea. It flew out of radar range 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in Malaysia’s northern Peninsular.

The disappearance of Flight 370 was the deadliest incident involving a Boeing 777 and the deadliest in Malaysia Airlines history until it was surpassed in both categories four months later on 17 July 2014 by Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down while flying over conflict-torn Eastern Ukraine. Malaysia Airlines, which was renationalized by the Malaysian government in August 2014, had major financial difficulties as a result of the combined loss.

The search for the missing plane, which became the most expensive in aviation history, initially focused on the South China Sea and the Andaman Sea, before analysis of the plane’s automated communications with an Inmarsat satellite revealed a possible crash site somewhere in the southern Indian Ocean. The absence of official information in the days following the disappearance drew harsh condemnation from the Chinese public, notably from families of the passengers, given that the majority of those on board Flight 370 were of Chinese ancestry. Several pieces of aeroplane wreckage werehed up on the shores of the western Indian Ocean in 2015 and 2016. After a three-year search across 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of water failed to find the plane, the Joint Agency Coordination Centre in charge of the operation ceased operations in January 2017. A second search, initiated in January 2018 by private contractor Ocean Infinity, likewise ended in failure six months later.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) initially proposed that a hypoxia event was the most likely cause given the available evidence, based primarily on analysis of data from the Inmarsat satellite with which the aircraft last communicated, though no consensus has been reached among investigators regarding this theory. Possible hijacking possibilities were examined at various phases of the inquiry, including crew involvement and suspicion of the plane’s cargo manifest; many disappearance hypotheses involving the aircraft have also been published in the media. The Malaysian Ministry of Transport’s final investigation, issued in July 2018, was inconclusive, but emphasised Malaysian ATC’s inability to connect with the aircraft immediately after it vanished. In the lack of a conclusive reason of disappearance, suggestions and rules invoking Flight 370 have mostly been designed to prevent a recurrence of the circumstances surrounding the loss. Increased battery life on underwater locating beacons, longer recording lengths on flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders, and revised requirements for aircraft location reporting over open ocean are among them.

Timeline

The Malaysia Airlines Boeing 777-200ER last had vocal contact with ATC at 01:19 MYT, 8 March (17:19 UTC, 7 March) when it was over the South China Sea, less than an hour after departure. It vanished from ATC radar screens at 01:22 MYT, but it was still tracked on military radar as it deviated sharply from its original northeastern course to head west and cross the Malay Peninsula, continuing on that course until it vanished from military radar range at 02:22 while over the Andaman Sea, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in northwestern Malaysia.

Aircraft

Flight 370 was piloted by a Boeing 777-2H6ER with the serial number 28420 and the registration 9M-MRO. It was the 404th Boeing 777 produced, flying for the first time on May 14, 2002, and was delivered new to Malaysia Airlines on May 31, 2002. The aircraft was powered by two Rolls-Royce Trent 892 engines and could carry a total of 282 people. It had collected 53,471.6 hours and 7,526 cycles (takeoffs and landings) in service: 22 and had been engaged in no serious incidents, albeit a minor mishap while taxiing at Shanghai Pudong International Airport in August 2012 resulted in a fractured wing tip. Its most recent “A check” maintenance was performed on February 23, 2014. All applicable Airworthiness Directives for the airframe and powerplant were met by the aircraft. On 7 March 2014, a standard maintenance operation of replenishing the crew oxygen system was done; an inspection of this procedure revealed nothing odd.

Passengers and crew members

The plane was carrying 12 Malaysian crew members and 227 passengers from 14 countries. Malaysia Airlines announced the names and nationalities of the passengers and crew on the day of the disappearance, based on the flight manifest. Later, the passenger list was amended to add two Iranians travelling on stolen Austrian and Italian passports.

Crew

All 12 crew members—two pilots and ten cabin personnel—were Malaysians.

- Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, 53, of Penang, was the pilot in command. In 1981, he joined Malaysia Airlines as a cadet pilot, and after training and getting his commercial pilot’s licence, he was promoted to second officer in 1983. In 1991, he was promoted to captain of Boeing 737-400 airliners, 1996 to captain of Airbus A330-300, and 1998 to captain of Boeing 777-200. He had been a type rating examiner and teacher since 2007. Zaharie has accumulated 18,365 hours of flight time.

- First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid, 27, was the co-pilot. In 2007, he joined Malaysia Airlines as a cadet pilot; after working as a second officer on Boeing 737-400 airliners, he was promoted to first officer on the Boeing 737-400 in 2010 and then to the Airbus A330-300 in 2012. In November 2013, he began his training as a Boeing 777-200 first officer. Trip 370 was his final training flight before being investigated on his next flight. Fariq has 2,763 hours of flight time under his belt.

Passengers

Among the 227 passengers, 153 were Chinese citizens, included a group of 19 artists, six family members, and four staff members returning from a calligraphy display of their work in Kuala Lumpur; 38 were Malaysians. The remaining passengers came from a total of 12 different nations. Twenty passengers, 12 from Malaysia and eight from China, were Freescale Semiconductor employees.

Tzu Chi (an worldwide Buddhist organisation) promptly dispatched highly trained teams to Beijing and Malaysia under a 2007 agreement with Malaysia Airlines to provide emotional support to passengers’ families. The airline also dispatched its own team of carers and volunteers and pledged to cover the costs of transporting passengers’ families to Kuala Lumpur and providing them with housing, medical care, and counselling. In total, 115 Chinese travellers’ family members travelled to Kuala Lumpur. Others in the family preferred to remain in China, thinking they would feel too alone in Malaysia.

Presumptive loss

At 07:24 MYT, one hour after the flight’s scheduled arrival time in Beijing, Malaysia Airlines issued a media statement stating that communication with the flight had been lost by Malaysian ATC at 02:40 and that the government had initiated search-and-rescue operations; the time when contact was lost was later corrected to 01:21.

Before the aircraft vanished from radar screens, neither the crew nor the aircraft’s communication systems transmitted a distress signal, signs of adverse weather, or mechanical difficulties. Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak made a statement about Flight 370 to the media on March 24 at 22:00 local time, stating that the Air Accidents Investigation Branch and Inmarsat (the satellite data provider) had concluded that the airliner’s last position before it vanished was in the southern Indian Ocean. The aeroplane must have crashed into the water because there were no landing spots available.

Sightings reported

Several sightings of an aircraft matching the specifications of the missing Boeing 777 were reported by the news media. On March 19, 2014, CNN claimed that witnesses included fisherman, an oil rig worker, and residents of the Maldives’ Kuda Huvadhoo atoll witnessed the missing aeroplane. A fisherman reported seeing an unusually low-flying aircraft off the coast of Kota Bharu, while an oil-rig worker 186 miles (299 km) southeast of Vung Tau reported seeing a “burning object” in the sky that morning, a claim credible enough for Vietnamese authorities to dispatch a search-and-rescue mission; and Indonesian fishermen reported seeing an aircraft crash near the Malacca Straits. The Daily Telegraph reported three months later that a British woman sailing in the Indian Ocean claimed to have witnessed an aircraft on fire.

Search

Soon after the loss of Flight 370, a search-and-rescue operation was initiated throughout Southeast Asia. One week after the aircraft went missing, the surface search was relocated to the southern Indian Ocean based on an early examination of communications between the aircraft and a satellite. Between March 18 and April 28, 19 boats and 345 military aircraft missions searched approximately 4,600,000 km2 (1,800,000 sq mi). The final stage of the search was a bathymetric survey and sonar scan of the sea bottom around 1,800 kilometres (970 nautical miles; 1,100 miles) southwest of Perth, Western Australia. With effect from 30 March 2014, the search was coordinated by the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC), an Australian government agency established specifically to manage the effort to locate and recovery of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which largely involves the Malaysian, Chinese, and Australian governments.

Technical background

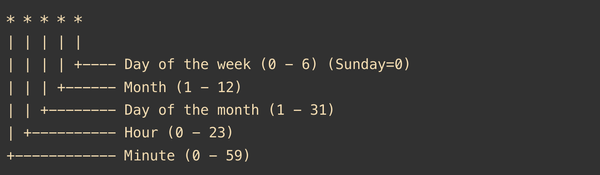

Aeronautical satellite communication (SATCOM) systems employ the ACARS communications protocol to send messages from the aircraft cockpit as well as automatic data signals from onboard equipment. SATCOM can also be used to send FANS and ATN communications, as well as provide voice, fax, and data links via various protocols. To send and receive signals through the satellite communications network, the aircraft employs a satellite data unit (SDU), which functions independently of the other onboard systems that connect via SATCOM, usually via the ACARS protocol. Signals from the SDU are broadcast to a communications satellite, which amplifies and adjusts the frequency of the signal before relaying it to a ground station, where it is analysed and If relevant, it is directed to its designated destination (for example, Malaysia Airlines’ operations centre); signals are transmitted from the ground to the aircraft in reverse order.